Table of Contents (click to expand)

Higher temperatures and lower rainfall due to climate change could impact the cacao trees in Africa, where 70% of cacao beans (used to make chocolate) come from. Fortunately, we do have a host of solutions already on hand.

Almost everyone around the world is discussing the disastrous effects of climate change and global warming on our planet; glaciers will melt, sea levels will rise, new diseases will appear, droughts and floods will destroy our habitats and farmlands, it will become too hot (or too cold) to farm, and much more.

Amidst all this, have you wondered whether, as the climate shifts, will we continue to have chocolate?

After all, “Chocolate is happiness that you can eat,” and happiness is kind of important, especially as the world (literally) burns.

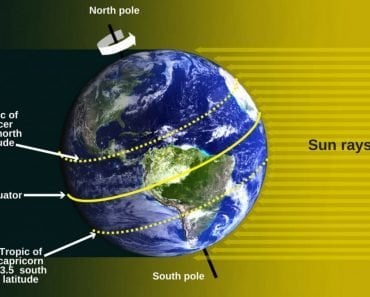

Chocolate is made from cacao beans that grow on cacao trees. Cacao trees thrive in uniform warm temperature, along with high humidity and rainfall, and they’re usually grown in rainforests in the region 20° north and south of the Equator. Since chocolates need high temperatures to grow, that should mean that they’ll thrive on a warmer Earth, right?

I wish it were that simple.

Along with the high temperatures, the trees also need high humidity. If the increase in temperatures in cacao-growing regions is not accompanied with an increase in humidity, cacao trees might find it challenging to thrive.

Recommended Video for you:

Where Does Chocolate Come From?

Chocolate is made from the cacao beans harvested from the cacao tree (Theobroma cacao). Theobroma cacao is an evergreen tree belonging to the family Malvaceae, the same family as cotton, okra and hibiscus.

The flowers are formed directly on the trunk and are pollinated by tiny flies. The oval fruits containing 30-50 seeds are harvested. The seeds (beans) are processed through an elaborate series of steps involving fermentation, drying, roasting, conching, tempering and molding before they reach the shelves of a store near you.

Around 70% of the world’s cacao beans come from the West African cacao belt (Sierra Leone to Southern Cameroon). This is the area where cacao originated and where most high-quality cacao is grown. Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana produce 53% of the world’s cocoa.

Is It Cacao Or Cocoa Or Chocolate?

Cacao refers to the tree, the pods, and the beans. Cocoa is the product we get after the beans are ground and roasted. Cocoa is also the name for the drink made from this ground powder. Chocolate is the product made by mixing cocoa, cocoa butter, and sugar.

Will It Be Too Hot For Cacao?

Climate change is expected to make the Earth approximately 2.1°C warmer by 2050. The predicted increase in temperature and its associated impact on rainfall will vary in different parts of the world.

Considering this, researchers have analyzed the climate vulnerability of the major cacao-growing regions.

Increases in temperature will cause the evaporation of water from the soil and evaporation of water from the stomata on the leaves (transpiration). Couple this with less rainfall (predicted), and the regions will experience drought stress in the dry season.

For example, most of the regions in the cacao belt currently have maximum temperatures < 35°C in the dry season. Using the climate prediction models, the researchers concluded that by 2050, temperatures in the range of 35-36°C will become common over large areas of the cocoa belt. However, the models also predict a shortening of the dry season. This means that the increasing temperatures will be accompanied by an increase in rainfall, except during the short dry season.

Even so, the higher temperatures will increase evaporation and transpiration, leading to drought-like conditions in the regions where cacao grows: in Nigeria, Cameroon and eastern Côte d’Ivoire. These are also the driest parts of the cocoa belt, making them poorly suited for cacao plants.

Drought is a bigger problem than heat. In some regions, the increase in temperature will be compensated by rainfall, but not everywhere.

Another study analyzed the suitability of 294 cacao-growing regions in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana based on climate change forecasts. They concluded that the higher temperatures and drier conditions will make large areas unsuitable for cacao cultivation. Only 10.5% of the current cacao-growing regions will continue to be suitable for cacao in 2050.

Can We Save Our Supply Of Happiness (Chocolate)?

Since we still have a few years until 2050, a long-term solution could be breeding cacao varieties with altered genetics that make them grow in spite of drought conditions and replace the current cacao plantations with these varieties.

Another measure could be to keep the heat out by keeping the plants in the shade. Planting tall rainforest trees around the cacao trees could be a way to reduce the impact of higher temperatures. The tall trees will provide dense shade canopy and protect the cacao trees from wind. The fallen leaves of these rainforest trees will also add nutrients to the soil. Shade from larger trees is estimated to reduce the temperature of the cacao leaves by up to 4°C.

This method of agroforestry is practiced in Brazil, where some cacao growers have densely shaded farms. The dense shade helps them control insect pressure and weeds, keeps the microclimate stable, and utilizes the litter from the trees to maintain soil fertility.

Shade trees can also help diversify farm products, help prevent soil erosion and aid in biodiversity conservation. In addition, crop diversification will reduce the dependence of the farmers on just one crop and reduce their vulnerability to changes in the local and regional climate.

Another solution could be to move the cacao cultivation areas to higher altitudes, where the temperatures will be lower. However, most of these higher altitude areas are covered with natural forests and extending cacao cultivation to these areas would mean cutting down these forests, further contributing to climate change.

Conclusion

Overall, the climate change models predict that while some cacao-growing regions will continue to be suitable for cacao production, large areas in eastern Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria and Cameroon will become too hot and dry. However, a combination of improved genetics and the adoption of agroforestry methods could help cacao growers become climate-resilient, ensuring that we can continue eating chocolate and being happy!

References (click to expand)

- Climate & Chocolate.

- Läderach, P., Martinez-Valle, A., Schroth, G., & Castro, N. (2013, May 23). Predicting the future climatic suitability for cocoa farming of the world’s leading producer countries, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. Climatic Change. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Johns, N. D. (1999, January 1). Conservation in Brazil's Chocolate Forest: The Unlikely Persistence of the Traditional Cocoa Agroecosystem. Environmental Management. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Schroth, G., Läderach, P., Martinez-Valle, A. I., Bunn, C., & Jassogne, L. (2016, June). Vulnerability to climate change of cocoa in West Africa: Patterns, opportunities and limits to adaptation. Science of The Total Environment. Elsevier BV.