Table of Contents (click to expand)

Many animals in the wild produce their own version of sunscreen lotion. Hippos’ make sweat with chemicals that absorb harmful UV radiation, while zebrafish produce a substance called gadusol that protects the fish and its eggs from UV damage.

Imagine going to a beach on a bright, sunny day, but you forgot to apply sunscreen—this is a common story with a painful ending for many with sensitive or fair skin.

A few hours in the sun without sunscreen can turn our skin into a painful red disaster that feels hot to the touch, but have you ever wondered if animals face a similar problem? Do they get tanned and sunburned? After all, they spend more extended hours than us, wandering in search of water and food in the unforgiving sun.

While a handy bottle of sunscreen can save us from the wrath of sunburn, is there anything that protects animals from getting scorched?

Recommended Video for you:

Do Animals Get Sunburn?

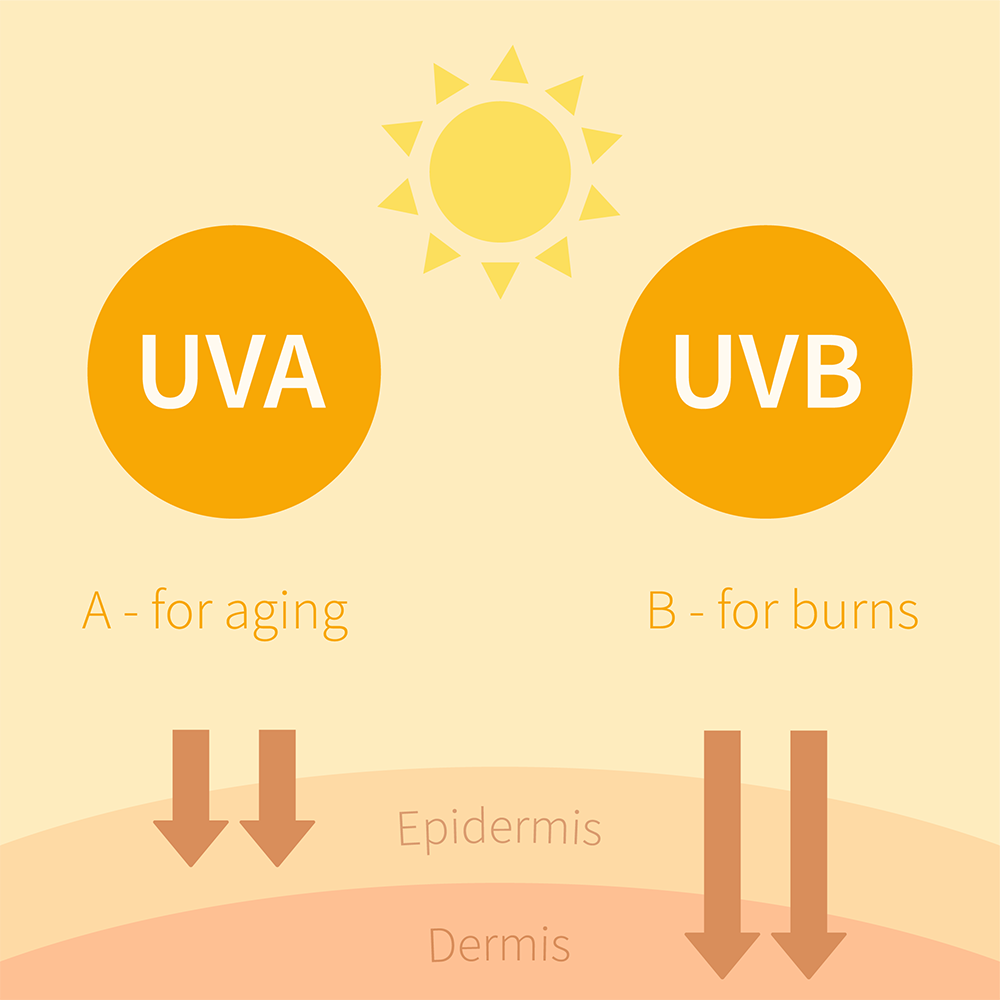

The culprit of sunburn is pretty apparent: the Sun. Prolonged exposure to the UV rays of the sun, mainly the UV-B rays, causes our skin to develop a sunburn.

And to answer the question, yes, animals do face the stinging feeling of sunburn. Just as humans stay protected by clothing and shade, so too does an animal’s fur keep the animal’s skin from harm. However, there are animals like pigs, hippos, rhinoceros, elephants and others that have very little hair covering their skin.

Without a layer of hair to protect them, these animals are left out in the cold, or to be precise, left out in the sun. When one door closes, however, nature opens a window: DIY sunscreen. Some animals have the gifted ability to create their own sunscreen.

The Red Sweat Of Hippos

Imagine that it’s a hot summer day and you can feel drops of water trickling down your forehead, while a dark and sometimes stinky wet patch forms on the sleeve under your armpit.

Sweat is common in most mammals, like monkeys and horses. Sweating, for the most part, helps in thermoregulation. It helps cool down the body on a hot sunny day.

However, unlike our sweat, which leaves us with an undesirable body odor, there is an animal whose sweat is of great value to them: Hippos, the big animals that look funny, but are actually angry all the time.

Hippopotamuses secrete blood-like sweat that protects their hairless skin from the harsh sun. The sweat is highly alkaline, with a pH range of 8.5-10.5, as compared to our sweat with a pH of around 6.3. That said, this secretion isn’t really sweat, so to speak. The viscous liquid is secreted from a subdermal gland, not from a sweat gland.

Initially, this secretion is colorless, but soon after exposure to the environment it turns red and then brown as the pigment gradually polymerizes. The pigments responsible for giving the secretion its blood-red identity were isolated and named hipposudoric acid (red pigment) and norhipposudoric acid (orange pigment).

The two pigments are the reason why hippos are perennially protected from the sun. The secretions absorb harmful UV rays (200-600nm), which makes it safe to say that they act as sunscreen. They also have antibiotic properties against some bacteria.

Do Fish Need Sun Protection?

You can clearly understand why animals wandering the land would require sun protection, but what about aquatic life? Given that they live almost exclusively underwater, do they risk getting sunburnt?

As improbable as it may seem, even in the depths of water, fish are exposed to harmful levels of UVB rays. The rays can penetrate to depths of over 10m in clear waters. Various organisms have their own way of adapting to avoid UV exposure. Some have a DNA repair mechanism that repairs the damage done by UV radiation.

However, these adaptions do not guarantee foolproof protection from UV damage. That’s why many aquatic organisms also produce their own sunscreen.

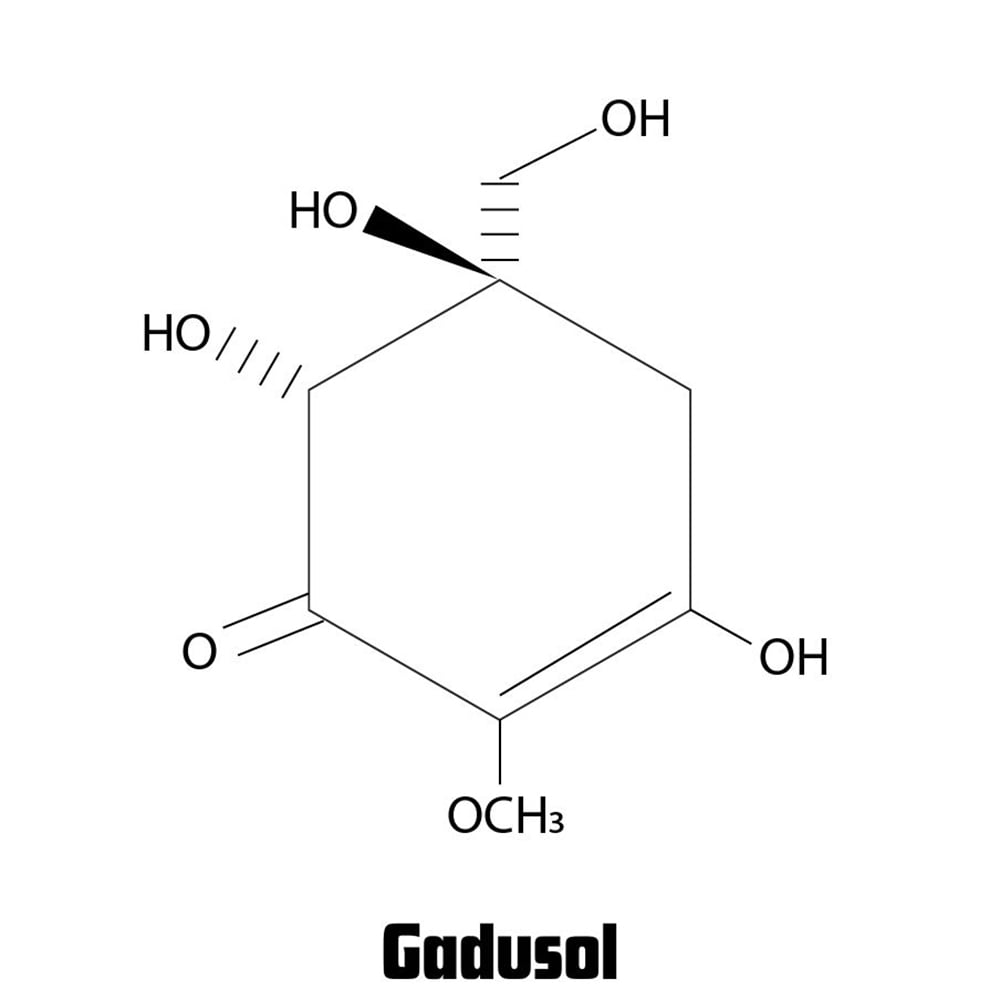

Gadusol

Animals, including humans, produce melanin that absorbs UV rays to protect the skin from sun damage. Fish and some other aquatic vertebrae have melanophores (similar to melanocytes in mammals) that produce melanin.

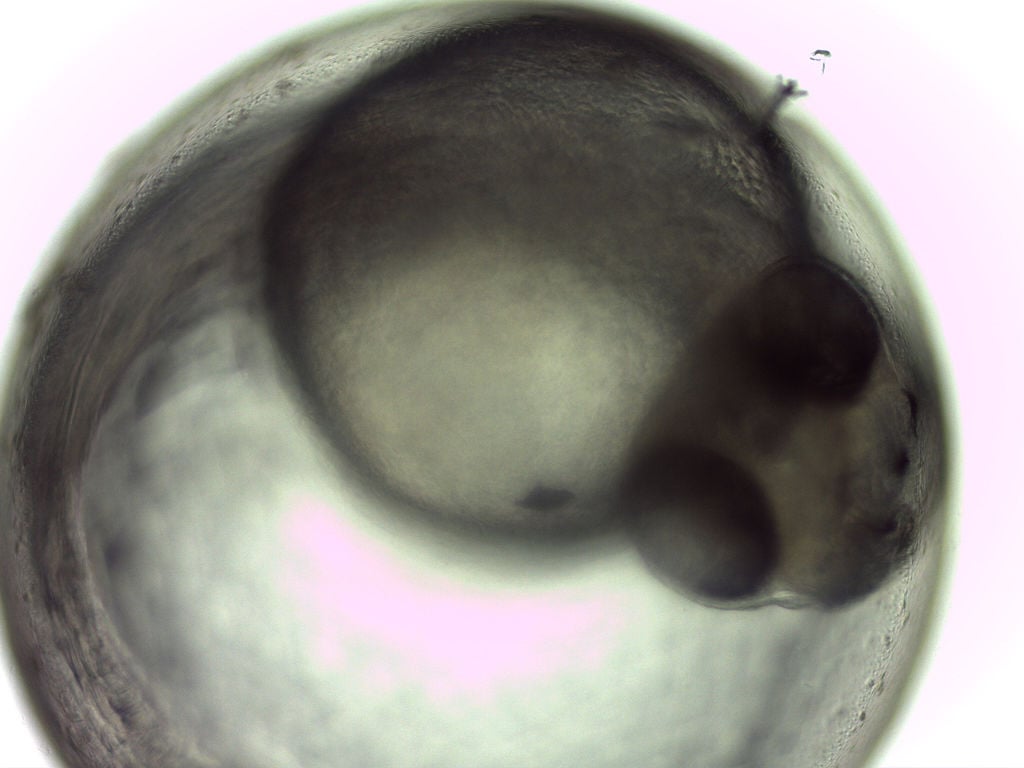

Although melanin does its job of sun protection, it is not the ideal sunscreen for a baby fish developing inside the egg, as melanophores appear late in the process of embryo development. Thus, the embryo in the early stages is left vulnerable to damage by harsh UV rays.

To counter this, a compound similar to Mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) called gadusol works to protect the eggs of some fish species. Mycosporine is a UV-absorbing compound mostly seen in fungi, algae and cyanobacteria.

A study found that a mother Zebrafish deposits gadusol on her eggs to protect them from UV damage. To verify the sunscreen property of gadusol, researchers created a zebrafish mutant that produces little to no gadusol and exposed it to UVB radiation. These fish suffered developmental defects due to sun exposure. They were unable to inflate their swim bladder, which helps maintain their buoyancy.

Gadusol and melanin both work well to absorb UVB radiation. However, gadusol also fares well when it comes to helping aquatic animals with camouflage. It is a common behavior among them, as there aren’t many things to take cover behind in the open ocean. Melanin absorbs more of the light from the visible spectrum than gadusol. This makes melanin opaque and easily visible, while gadusol remains transparent and invisible.

Thanks to gadusol, an organism can remain inconspicuous, while also enjoying the benefits of nutrient-rich sunlit areas underwater. Thus, gadusol acts as a primary sunscreen for a developing fish, while melanin provides secondary protection from the sun.

Conclusion

Humans have the luxury of creating artificial sunscreens to shield our skin from sun damage. There are a select few animals with the ability to secrete their own sunscreen without any external help, but what about the remaining animals? How do they keep painful sunburns at bay? Well, let’s just that animals are resourceful beings. Elephants and rhinos roll around in the mud to stay protected from the sun. At the same time, other animals like chimpanzees, gorillas and koalas are smart enough to sleep during the high-sun hours and work in the early morning and at night.

References (click to expand)

- Saikawa, Y., Hashimoto, K., Nakata, M., Yoshihara, M., Nagai, K., Ida, M., & Komiya, T. (2004, May). The red sweat of the hippopotamus. Nature. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Hashimoto, K., Saikawa, Y., & Nakata, M. (2007, January 1). Studies on the red sweat of the Hippopotamus amphibius. Pure and Applied Chemistry. Walter de Gruyter GmbH.

- Rice, M. C., Little, J. H., Forrister, D. L., Machado, J., Clark, N. L., & Gagnon, J. A. (2023, August). Gadusol is a maternally provided sunscreen that protects fish embryos from DNA damage. Current Biology. Elsevier BV.

- Rice, M. C., Little, J. H., Forrister, D. L., Machado, J., Clark, N. L., & Gagnon, J. A. (2023, January 31). Gadusol is a maternally provided sunscreen that protects fish embryos from DNA damage. []. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

- Rice, M. C., Little, J. H., Forrister, D. L., Machado, J., Clark, N. L., & Gagnon, J. A. (2023, August). Gadusol is a maternally provided sunscreen that protects fish embryos from DNA damage. Current Biology. Elsevier BV.